In an article in Occupied Times Rufus May announces his plans to leave the NHS [National Health Service] in UK where he attempted, for eighteen years working as a clinical psychologist to bring change to services from the inside – by “infiltrating with loving kindness”. In that time, as he says, he has seen many pockets of change for the good but does not see that things have gotten better overall.

Rufus is now chooing to work “promoting more emancipatory approaches”.

These days the asylum is less noticeable as bricks and mortar establishments on the edge of town than it is recognizable as a shared mentality of attitudes and fears, of forms of segregation and control that range from the subtle and invisible to the often heavy-handed use of medications.

Rufus outlines some of his ideas for what we will need to change beyond simply changing what we often call “mental health services” if we are going to increase our chances of improving individual and collective well being, ideas like:

- breaking free from our own need to suppose that we can know what’s best for others, and from our reliance on ways of communicating that are rooted in fear and control.

- escaping the asylum mentality that separates us into two groups – those of us that are called “mad” and cast into the asylum can never be allowed to be free yet may act more freely than those outside; meanwhile, those of us that are not “mad” also cannot allow themselves to be free because they must at all times give every appearance of rational control even while fighting of fears of they too falling into madness.

- releasing ourselves from fear and recognize that we all have many experiences including anxieties and delusions, we all can and do suffer and we all have much wisdom.

- becoming curious about the meanings of experiences we call madness and “mental illness” rather than battle to eradicate every uncomfortable experience

- recognizing the social roots of people’s difficulties like poverty, violence in the home, broken relationships, bereavement and learn how to help people overcome them, to reconnect with themselves and community.

- bringing the community into the asylum and bring the asylum and conversations about madness and distress out into the community so we can talk about what helps us survive trauma and what helps with healing and recovery.

- working preventively, looking at how we relate as equals and creating spaces in which we can learn less violent ways of living amongst each other.

promote more emancipatory approaches to mental health. – See more at: http://theoccupiedtimes.org/?p=12770#sthash.DavdpJZh.dpuf

Rufus May will be joining us in Toronto in June14 for the international conference

Psychosis 2.0

Psychosis 2.0

New Understandings, ways of working with and healing from psychosis.

Friday 13th June 2014

Toronto

you can be there too…

Registration http://psychosis2.wordpress.com/registration/

Escaping The Asylum Mentality

by Rufus May

I am leaving the NHS after 18 years of working inside it as a clinical psychologist. I now want to try to work outside it to promote more emancipatory approaches to mental health.

Originally, I had the idea of infiltrating the mental health system with loving kindness. I had fairly briefly been embroiled in the mental health system as a patient at the age of 18. Moved by how little people were being heard and understood within that system, I went on to train as a psychologist keen to prove that there were alternatives to labelling and drugging people. And while I’ve seen (and feel like I have been part of) pockets of good things inside the mental health system, I don’t see it getting particularly better. Some things were better ten years ago, some things were worse. Overall, I think we need to change how society operates to improve people’s chances of greater well-being. We need to break free from paternalistic ways of relating and our own fearful compliance with punitive and controlling styles of communication.

How do we escape the confinements of the asylum mentality? The asylum was all about the exclusion and control of those people who were not mentally in tune enough with society’s values, even if they hadn’t broken any law. But the asylum mentality also had an effect on those who were not confined within its walls. To be “not mad” came at a price, we had to deny our ‘’irrational’’ feelings and our desires to break free of restrictive social norms.

In modern times we have briefer psychiatric hospital admissions for most, but many institutionalising dynamics remain and proliferate. Grading people is an old colonial technique of divide and rule. If you categorise someone with a psychiatric diagnosis it can become a way of trying to control them and shape how they think about themselves. Then we have the heavy-handed use of psychotropic drugs; not just to give someone a temporary break from their difficulties, but for those in power to promote the long-term suppression of challenging thoughts and emotions with the latest profit-making pharmaceutical product. In the general population we too encourage each other to be comfortably numb with alcohol, and other mediums effective at creating distracted states of mind.

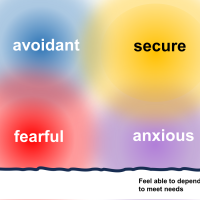

We need to give up thinking in terms of mental illness and mental wellness as either/or categories. We all have delusions and anxieties, we all suffer, yet we also all have moments of awareness and great wisdom. The ‘them and us’ divide restricts people on both sides of the illness/wellness polarisation. For example, recently an ex-psychiatric nurse expressed to me how she had been jealous of the psychiatric patients on the ward she worked on because of the way they had freely been themselves and helped each other. She, on the other hand, felt policed to not share her vulnerabilities but rather to pose as a fairly wooden character: the sane and detached mental health professional.

We need to be curious about the meanings that lie buried in what gets called mental illness, rather than distance ourselves from it. The mental health problem is a messenger that needs to be recognised, not battled with. For example, self-hatred tells us the person had to turn anger in on themselves to survive. We need to acknowledge this survival skill before encouraging new ways to take care of feelings and interact with the world. Similarly, delusional thinking rescues us temporarily from painful feelings or it creates a filter through which those feelings can be felt in a manageable way. If I believe I am a Jedi Knight fighting dark forces which are out to get me, this can symbolise bullying I have been through that I feel too embarrassed or loyal to family honour to talk about.

If we start to hear aggressive domineering voices this may echo bullying relationships we have experienced in the past. In “Hearing Voices” self-help groups, we find that people can change the relationship with their voices by learning new ways to deal with emotional conflict. So madness makes sense yet huge sections of society, including the establishment, have forgotten this. It’s convenient if we forget the social causes of mental anguish because then you don’t have to question and rethink how we as a society are doing things.

Recently, I have been working with several angry young men. They are angry because people have let them down. My job is to help them reconnect with themselves and their community. I try to do this by building trust, empathising and helping them find ways they can channel and control their aggression and ultimately learn to be more gentle with their emotions.

Working with young people makes it easier to see the social roots of their difficulties: Poor schooling experiences, controlling power relationships, parents with addiction problems, poverty, violence in the home, broken relationships, bereavements that have not been addressed, to name but a few. The clues to the social toxins underlying people’s emotional difficulties lie in their life stories. The solutions appear to me to be social too. Fundamentally, it’s all about relationship building. Even though I am a psychologist, I don’t think it’s all about one-to-one talking therapies. For instance, I have found that physical activities like martial arts and traditional farming skills like drystone walling and scything have a huge impact on rebuilding people’s confidence and connectedness.

To escape the asylum we have to bring the community into the asylum and the asylum into the community. This means pub evenings where we talk about living with paranoia, school sessions on how we survive trauma and what helps healing and recovery. Why not have schools visit psychiatric hospitals? We also need to work preventively. That means looking at how we relate to each other as equals, creating spaces where we can all learn less violent ways to relate to each other together.

See more at:

http://theoccupiedtimes.org/?p=12770#sthash.DavdpJZh.dpuf

Occupied Times

I am leaving the NHS after 18 years of working inside it as a clinical psychologist. I now want to try to work outside it to promote more emancipatory approaches to mental health.

Originally, I had the idea of infiltrating the mental health system with loving kindness. I had fairly briefly been embroiled in the mental health system as a patient at the age of 18. Moved by how little people were being heard and understood within that system, I went on to train as a psychologist keen to prove that there were alternatives to labelling and drugging people. And while I’ve seen (and feel like I have been part of) pockets of good things inside the mental health system, I don’t see it getting particularly better. Some things were better ten years ago, some things were worse. Overall, I think we need to change how society operates to improve people’s chances of greater well-being. We need to break free from paternalistic ways of relating and our own fearful compliance with punitive and controlling styles of communication.

How do we escape the confinements of the asylum mentality? The asylum was all about the exclusion and control of those people who were not mentally in tune enough with society’s values, even if they hadn’t broken any law. But the asylum mentality also had an effect on those who were not confined within its walls. To be “not mad” came at a price, we had to deny our ‘’irrational’’ feelings and our desires to break free of restrictive social norms.

In modern times we have briefer psychiatric hospital admissions for most, but many institutionalising dynamics remain and proliferate. Grading people is an old colonial technique of divide and rule. If you categorise someone with a psychiatric diagnosis it can become a way of trying to control them and shape how they think about themselves. Then we have the heavy-handed use of psychotropic drugs; not just to give someone a temporary break from their difficulties, but for those in power to promote the long-term suppression of challenging thoughts and emotions with the latest profit-making pharmaceutical product. In the general population we too encourage each other to be comfortably numb with alcohol, and other mediums effective at creating distracted states of mind.

We need to give up thinking in terms of mental illness and mental wellness as either/or categories. We all have delusions and anxieties, we all suffer, yet we also all have moments of awareness and great wisdom. The ‘them and us’ divide restricts people on both sides of the illness/wellness polarisation. For example, recently an ex-psychiatric nurse expressed to me how she had been jealous of the psychiatric patients on the ward she worked on because of the way they had freely been themselves and helped each other. She, on the other hand, felt policed to not share her vulnerabilities but rather to pose as a fairly wooden character: the sane and detached mental health professional.

We need to be curious about the meanings that lie buried in what gets called mental illness, rather than distance ourselves from it. The mental health problem is a messenger that needs to be recognised, not battled with. For example, self-hatred tells us the person had to turn anger in on themselves to survive. We need to acknowledge this survival skill before encouraging new ways to take care of feelings and interact with the world. Similarly, delusional thinking rescues us temporarily from painful feelings or it creates a filter through which those feelings can be felt in a manageable way. If I believe I am a Jedi Knight fighting dark forces which are out to get me, this can symbolise bullying I have been through that I feel too embarrassed or loyal to family honour to talk about.

If we start to hear aggressive domineering voices this may echo bullying relationships we have experienced in the past. In “Hearing Voices” self-help groups, we find that people can change the relationship with their voices by learning new ways to deal with emotional conflict. So madness makes sense yet huge sections of society, including the establishment, have forgotten this. It’s convenient if we forget the social causes of mental anguish because then you don’t have to question and rethink how we as a society are doing things.

Recently, I have been working with several angry young men. They are angry because people have let them down. My job is to help them reconnect with themselves and their community. I try to do this by building trust, empathising and helping them find ways they can channel and control their aggression and ultimately learn to be more gentle with their emotions.

Working with young people makes it easier to see the social roots of their difficulties: Poor schooling experiences, controlling power relationships, parents with addiction problems, poverty, violence in the home, broken relationships, bereavements that have not been addressed, to name but a few. The clues to the social toxins underlying people’s emotional difficulties lie in their life stories. The solutions appear to me to be social too. Fundamentally, it’s all about relationship building. Even though I am a psychologist, I don’t think it’s all about one-to-one talking therapies. For instance, I have found that physical activities like martial arts and traditional farming skills like drystone walling and scything have a huge impact on rebuilding people’s confidence and connectedness.

To escape the asylum we have to bring the community into the asylum and the asylum into the community. This means pub evenings where we talk about living with paranoia, school sessions on how we survive trauma and what helps healing and recovery. Why not have schools visit psychiatric hospitals? We also need to work preventively. That means looking at how we relate to each other as equals, creating spaces where we can all learn less violent ways to relate to each other together.

– See more at: http://theoccupiedtimes.org/?p=12770#sthash.DavdpJZh.dpuf

I am leaving the NHS after 18 years of working inside it as a clinical psychologist. I now want to try to work outside it to promote more emancipatory approaches to mental health.

Originally, I had the idea of infiltrating the mental health system with loving kindness. I had fairly briefly been embroiled in the mental health system as a patient at the age of 18. Moved by how little people were being heard and understood within that system, I went on to train as a psychologist keen to prove that there were alternatives to labelling and drugging people. And while I’ve seen (and feel like I have been part of) pockets of good things inside the mental health system, I don’t see it getting particularly better. Some things were better ten years ago, some things were worse. Overall, I think we need to change how society operates to improve people’s chances of greater well-being. We need to break free from paternalistic ways of relating and our own fearful compliance with punitive and controlling styles of communication.

How do we escape the confinements of the asylum mentality? The asylum was all about the exclusion and control of those people who were not mentally in tune enough with society’s values, even if they hadn’t broken any law. But the asylum mentality also had an effect on those who were not confined within its walls. To be “not mad” came at a price, we had to deny our ‘’irrational’’ feelings and our desires to break free of restrictive social norms.

In modern times we have briefer psychiatric hospital admissions for most, but many institutionalising dynamics remain and proliferate. Grading people is an old colonial technique of divide and rule. If you categorise someone with a psychiatric diagnosis it can become a way of trying to control them and shape how they think about themselves. Then we have the heavy-handed use of psychotropic drugs; not just to give someone a temporary break from their difficulties, but for those in power to promote the long-term suppression of challenging thoughts and emotions with the latest profit-making pharmaceutical product. In the general population we too encourage each other to be comfortably numb with alcohol, and other mediums effective at creating distracted states of mind.

We need to give up thinking in terms of mental illness and mental wellness as either/or categories. We all have delusions and anxieties, we all suffer, yet we also all have moments of awareness and great wisdom. The ‘them and us’ divide restricts people on both sides of the illness/wellness polarisation. For example, recently an ex-psychiatric nurse expressed to me how she had been jealous of the psychiatric patients on the ward she worked on because of the way they had freely been themselves and helped each other. She, on the other hand, felt policed to not share her vulnerabilities but rather to pose as a fairly wooden character: the sane and detached mental health professional.

We need to be curious about the meanings that lie buried in what gets called mental illness, rather than distance ourselves from it. The mental health problem is a messenger that needs to be recognised, not battled with. For example, self-hatred tells us the person had to turn anger in on themselves to survive. We need to acknowledge this survival skill before encouraging new ways to take care of feelings and interact with the world. Similarly, delusional thinking rescues us temporarily from painful feelings or it creates a filter through which those feelings can be felt in a manageable way. If I believe I am a Jedi Knight fighting dark forces which are out to get me, this can symbolise bullying I have been through that I feel too embarrassed or loyal to family honour to talk about.

If we start to hear aggressive domineering voices this may echo bullying relationships we have experienced in the past. In “Hearing Voices” self-help groups, we find that people can change the relationship with their voices by learning new ways to deal with emotional conflict. So madness makes sense yet huge sections of society, including the establishment, have forgotten this. It’s convenient if we forget the social causes of mental anguish because then you don’t have to question and rethink how we as a society are doing things.

Recently, I have been working with several angry young men. They are angry because people have let them down. My job is to help them reconnect with themselves and their community. I try to do this by building trust, empathising and helping them find ways they can channel and control their aggression and ultimately learn to be more gentle with their emotions.

Working with young people makes it easier to see the social roots of their difficulties: Poor schooling experiences, controlling power relationships, parents with addiction problems, poverty, violence in the home, broken relationships, bereavements that have not been addressed, to name but a few. The clues to the social toxins underlying people’s emotional difficulties lie in their life stories. The solutions appear to me to be social too. Fundamentally, it’s all about relationship building. Even though I am a psychologist, I don’t think it’s all about one-to-one talking therapies. For instance, I have found that physical activities like martial arts and traditional farming skills like drystone walling and scything have a huge impact on rebuilding people’s confidence and connectedness.

To escape the asylum we have to bring the community into the asylum and the asylum into the community. This means pub evenings where we talk about living with paranoia, school sessions on how we survive trauma and what helps healing and recovery. Why not have schools visit psychiatric hospitals? We also need to work preventively. That means looking at how we relate to each other as equals, creating spaces where we can all learn less violent ways to relate to each other together.

– See more at: http://theoccupiedtimes.org/?p=12770#sthash.DavdpJZh.dpuf

I am leaving the NHS after 18 years of working inside it as a clinical psychologist. I now want to try to work outside it to promote more emancipatory approaches to mental health.

Originally, I had the idea of infiltrating the mental health system with loving kindness. I had fairly briefly been embroiled in the mental health system as a patient at the age of 18. Moved by how little people were being heard and understood within that system, I went on to train as a psychologist keen to prove that there were alternatives to labelling and drugging people. And while I’ve seen (and feel like I have been part of) pockets of good things inside the mental health system, I don’t see it getting particularly better. Some things were better ten years ago, some things were worse. Overall, I think we need to change how society operates to improve people’s chances of greater well-being. We need to break free from paternalistic ways of relating and our own fearful compliance with punitive and controlling styles of communication.

How do we escape the confinements of the asylum mentality? The asylum was all about the exclusion and control of those people who were not mentally in tune enough with society’s values, even if they hadn’t broken any law. But the asylum mentality also had an effect on those who were not confined within its walls. To be “not mad” came at a price, we had to deny our ‘’irrational’’ feelings and our desires to break free of restrictive social norms.

In modern times we have briefer psychiatric hospital admissions for most, but many institutionalising dynamics remain and proliferate. Grading people is an old colonial technique of divide and rule. If you categorise someone with a psychiatric diagnosis it can become a way of trying to control them and shape how they think about themselves. Then we have the heavy-handed use of psychotropic drugs; not just to give someone a temporary break from their difficulties, but for those in power to promote the long-term suppression of challenging thoughts and emotions with the latest profit-making pharmaceutical product. In the general population we too encourage each other to be comfortably numb with alcohol, and other mediums effective at creating distracted states of mind.

We need to give up thinking in terms of mental illness and mental wellness as either/or categories. We all have delusions and anxieties, we all suffer, yet we also all have moments of awareness and great wisdom. The ‘them and us’ divide restricts people on both sides of the illness/wellness polarisation. For example, recently an ex-psychiatric nurse expressed to me how she had been jealous of the psychiatric patients on the ward she worked on because of the way they had freely been themselves and helped each other. She, on the other hand, felt policed to not share her vulnerabilities but rather to pose as a fairly wooden character: the sane and detached mental health professional.

We need to be curious about the meanings that lie buried in what gets called mental illness, rather than distance ourselves from it. The mental health problem is a messenger that needs to be recognised, not battled with. For example, self-hatred tells us the person had to turn anger in on themselves to survive. We need to acknowledge this survival skill before encouraging new ways to take care of feelings and interact with the world. Similarly, delusional thinking rescues us temporarily from painful feelings or it creates a filter through which those feelings can be felt in a manageable way. If I believe I am a Jedi Knight fighting dark forces which are out to get me, this can symbolise bullying I have been through that I feel too embarrassed or loyal to family honour to talk about.

If we start to hear aggressive domineering voices this may echo bullying relationships we have experienced in the past. In “Hearing Voices” self-help groups, we find that people can change the relationship with their voices by learning new ways to deal with emotional conflict. So madness makes sense yet huge sections of society, including the establishment, have forgotten this. It’s convenient if we forget the social causes of mental anguish because then you don’t have to question and rethink how we as a society are doing things.

Recently, I have been working with several angry young men. They are angry because people have let them down. My job is to help them reconnect with themselves and their community. I try to do this by building trust, empathising and helping them find ways they can channel and control their aggression and ultimately learn to be more gentle with their emotions.

Working with young people makes it easier to see the social roots of their difficulties: Poor schooling experiences, controlling power relationships, parents with addiction problems, poverty, violence in the home, broken relationships, bereavements that have not been addressed, to name but a few. The clues to the social toxins underlying people’s emotional difficulties lie in their life stories. The solutions appear to me to be social too. Fundamentally, it’s all about relationship building. Even though I am a psychologist, I don’t think it’s all about one-to-one talking therapies. For instance, I have found that physical activities like martial arts and traditional farming skills like drystone walling and scything have a huge impact on rebuilding people’s confidence and connectedness.

To escape the asylum we have to bring the community into the asylum and the asylum into the community. This means pub evenings where we talk about living with paranoia, school sessions on how we survive trauma and what helps healing and recovery. Why not have schools visit psychiatric hospitals? We also need to work preventively. That means looking at how we relate to each other as equals, creating spaces where we can all learn less violent ways to relate to each other together.

– See more at: http://theoccupiedtimes.org/?p=12770#sthash.DavdpJZh.dpuf

Reblogged this on both sides of the wall and commented:

Interesting.

LikeLike

Hi Samantha Jane. Thanks for sharing, glad you find interesting.

LikeLike

Of my many life learning experiences, I struggled for many years to become free from the victim mentality. Indeed, learning not to regard myself as a victim proved to be helpful in preventing further victimization. Just something to think/write about?

LikeLike

🙂

LikeLike