Report in UK Guardian of a new research study first published by the British Medical Journal….

The study demonstrates that current antipsychotic-first approaches typically used in early intervention programmes are no more effective than other “benign” therapies and that, anyhoo, the numbers of people identified by screening as being at risk who do go on to develp more severe forms of psychosis are much less than thought.

The study also questions if the additial risk introduced y and the expense of typical early intervention programmes that are heavily reliant on administering antipsychotics are as justified as is conventionally thought.

Currently typical early psychosis intervention programmes are based in risk control – it is conventionally thought that 40-50% go on to develop more serious conditions. This is used to justify the current practice which seeks to manage that risk by “interrupting transmission” to more sever conditions with early treatment with then life-long maintenance on antipsychotics – with all the attendant risks that come with such free use of such powerful drugs.

This study not only shows that of people between 15 and 35 who exhibit early signs of psychosis the proportion that do go on to develop more serious conditions is only 8% .

Furthermore the study shows that “benign” approaches like talk therapies are as more effective at reducing severity of future experiences and introduce less additional biological risk.

Antipsychotics not first choice teatment

The study concludes that antpsychotics ought not be regarded as the first choice treatment and advises that practitioners exercise extreme care when prescribing anti-psychotics to young people.

The study finds that the neither intervention – antipsychotics nor cognitive thrapy significantly reduced the “transmission to” more serious conditions but that the cognitive therapy did lead to less severe experiences in future episodes.

The research indicates that both the risk of developing more serious forms of psychosis was much lower and that the potential for spontaneous healing without any theapeutic intervention was much higher that previously thought .

Guardian…

- Only 8% of of young people exhibiting early signs of psychosis go on to develop more serious conditions

- Clinicians should be “extremely careful” about prescribing anti-psychotics to young people

- Anti-psychotic medicine should not be the first option

“Counselling and therapies effective in treating psychotic experiences that can lead to conditions such as schizophrenia”

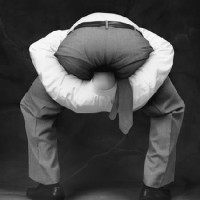

Anti-psychotic medicine aren’t always the best choice and shouldn’t be used as first option, study says. Photograph: INSADCO Photography /Alamy

Anti-psychotic medicine aren’t always the best choice and shouldn’t be used as first option, study says. Photograph: INSADCO Photography /Alamy

Anti-psychotic medicine should not be the first option offered to people at risk of developing schizophrenia, researchers said on Friday.

Clinicians should be “extremely careful” about prescribing anti-psychotics to young people, because only a tenth will go on to develop more serious conditions, a study suggests.

The study by five universities found that “benign” psychological treatments, including Cognitive Therapy (CT), were effective in reducing the severity of psychotic experiences that can lead to conditions such as schizophrenia.

Published on the British Medical Journal website bmj.com, the study found the frequency, seriousness, and intensity of psychotic symptoms that may lead to more serious conditions was reduced by counselling and CT.

The landmark research could pave the way for coherent treatment for young people at risk of developing psychotic illnesses.

Teams from the universities of Glasgow, Birmingham, Cambridge and East Anglia, led by the University of Manchester, gave participants, aged between 14 and 35, weekly CT sessions for a maximum of six months, over a four year period.

They then monitored participants after treatment to track their symptoms.

Before the trial, international evidence estimated that 40-50% of people at risk of developing psychosis at a young age would progress to a psychotic illness.

But only 8% of patients in the study were shown to have made the transition.

Researchers said the results have led to suggestions that anti-psychotic medicine should not be the first option for young patients.

Professor Andrew Gumley, who led the research team at the University of Glasgow, said: “This study has very important implications for ensuring that young people who are at risk of developing psychosis are offered psychological therapy.

“Our findings that there is a much lower transition rate than previously found means that clinicians have to be extremely careful about prescribing anti-psychotics in this group since only one in 10 will actually develop psychosis.”

BMJ

Extract from report published BMJ.comEarly detection and intervention evaluation for people at risk of psychosis: multisite randomised controlled trial

BMJ2012;344doi: 10.1136/bmj.e2233(Published 5 April 2012)

What is already known on this topic

-

It seems possible to identify a population at ultra high risk of developing psychosis

-

Several small trials suggest promising interventions for the prevention of psychosis and improvement in psychotic symptoms in these populations

What this study adds

-

Cognitive therapy did not prevent transition to psychosis but did reduce the severity of psychotic symptoms in young people (aged 14-35) at risk of psychosis

-

The rates of transition are lower than previously thought and there is a high potential for recovery with minimal intervention in this population

-

It is important to reconsider whether young people meeting these criteria can be accurately described as being at “ultra high risk of psychosis”

Read for yourself…

Guardian Article

BMJ.com : Early detection and intervention evaluation for people at risk of psychosis: multisite randomised controlled trial

Related articles

- New advice on treating psychosis (scotsman.com)

- Study: anti-psychotics should be avoided in young people (beyondmeds.com)

- New Study on a Non-Toxic Intervention for Those at High Risk of Psychosis (madinamerica.com)

- Call for caution over use of antipsychotics (yorkshirepost.co.uk)